Sitka, Alaska is a small tourist town on Baranof Island and neighboring Chichagof Island. The only access is by boat or plane. About nine thousand Alaskans call it home. Under Czarist Russian rule the island was known as New Archangel Island. The big Orthodox church in the middle of town stands out as both unusual and indigenous. These people were Russians for over sixty years, after they were Tlingit Indian for many centuries. Sitka was designated the official capital of Russian America in 1808. When the United States, through Secretary of State William Sewall bought Alaska (for $7.2 million; 2 cents/acre) from the Russians in 1867, the official transfer took place in Sitka.

Downtown looks like all the other towns on the cruise – you disembark, walk around and shop at stores catering to tourists, selling gold jewelry, T-shirts, mugs, postcards. The magic happens outside town.

If you’ve walked the giant Sequoia or Redwood forests of the Pacific coast, you’ve seen the largest and tallest trees in the world. I’d been there, done that. But I was not prepared for what greeted me as we entered the Sitka Spruce forest of Baranof Island. The Sitka Spruce is, of course, a conifer, related to both the aforementioned giants, and is fifth in line for the tallest tree on the globe. They seem to close in over you, standing at nearly three hundred feet. That is one whole football field up. And there are lots of them. Large Sitka Spruce stands can be found in Washington, California, Oregon, Vancouver Island and in continental Pacific Canada. Trees have been successfully transplanted to Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Iceland and Norway. They took to the Norwegian climate so well that it is now considered an invasive species.

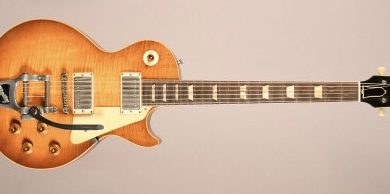

In 1721, when Antonio Stradivari carved the top for what would, centuries later, become known as the Lady Blunt violin (Lady Ann Blunt, grandchild of Lord Byron, owned the violin for 30 years), he certainly only considered one species of wood – Spruce. In 2011, the Lady Blunt violin sold at auction for 15.9 million dollars. Spruce can be a wonderful, vibrant tonewood, some species more than others. Among the best are Adirondack (red): Picea rubens, high altitude, slow-growth Engelmann (white) Picea Engelmannii, and Sitka (including Bearclaw): Picea sitchensis. Archtop guitars rely on spruce for their carved, and then tap tuned tops, usually on maple bodies. And spruce is the go-to top for flat-top construction as well. Flat-tops have many other options, koa, cedar and mahogany are popular for guitar tops, often paired with bodies of the same wood. Still, the large majority of guitars have spruce tops. Most players have, or used to have an acoustic guitar with a laminated body and solid spruce top.

Today a guitar builder can choose from all kinds of exotic woods for a body: striped ebony, Brazilian rosewood, Sinker Mahogany, Beeswax Maple, Cocobolo, The Log and so on from around the world. But more often than not, when you are putting your hard earned money into an exotic tonewood guitar, you want it to sound great. You want it quick to respond, you want it bright and you want it mellow, you want it eager to sing in your hands, alive to your touch – you want Sitka or Red Spruce on top. That is what it does. It sings and sustains so much, after just a tap, you can literally tune it with a pocket knife and sand paper. There is a reason why builders of stringed instruments, from Antonio Stradivari to Christian Friederich Martin selected spruce to top their hand made sound chambers.

Bearclaw

The variant of Sitka Spruce we know as Bearclaw Sitka presents a scarred or clawed appearance, which can break up the straight grain in attractive ways. It’s still the same Sitka, showing tracks left by a tiny boring parasite. Same vibrations, same response.

Following extensive lumbering for paper pulp, the Central Appalachian Spruce Restoration Initiative has begun replanting the once great Spruce forests of the higher elevation Appalachian Mountains. West Virginia dropped from 1.5 million acres in Adirondack Spruce to only 12,000 acres in forty years between 1880 and 1920. So now Adirondack Spruce, also commonly known as Red Spruce, a popular Christmas Tree, is becoming rare and needs our protection.

Gigantic Sitka trees, on the other hand, appear to be abundant, despite a century of logging for timber. You stand next to one tree, fifteen feet around, you look up three hundred feet into the sky to the top, and you wonder how many book-end matched, quarter sawn tops are we looking at? More than a lifetime’s worth of tonewood for any single luthier. Probably enough for the entire Gibson Acoustic manufacturing plant in Bozeman. For the next ten years.

While the giant trees are nowhere near as abundant now as they were in 1880, as we become more ecologically sensitive and careful, it’s a safe bet, they’ll be around a while. And one of them will sound great on the top of your next guitar.

Erol the Ottoman

We moved from Boston to Tiny-Town Indiana in 1980. Tiny-town had a few banks, enough retail and coffeeshops, grocery stores and funeral homes to almost sustain a “downtown” block or two. But when someone new came to town, it was news. We assimilated well. I joined the Rotary Club. Along the way I picked up a loose friendship with Erol.

Erol was a bit older. I was only 27, it was easy to be older. We were both athletic, and became tennis partners. Or tennis rivals as it were. I was good enough to provide Erol a game opponent, not good enough that he didn’t enjoy winning most of our matches. We played often over several summers and we became friends on deeper levels. We drove over to Ohio to watch a tennis tournament. We met Jimmy Connors and Erol pointed out a teen aged Venus Williams, told me to watch for her and her sister as they grew up. We talked about poetry. I still have a book of verse he gave me. I think we were both starved a bit for what I can only call, “cosomopolitan company.” Now, that sounds snobbish. But Erol had grown up in Turkey. He looked like me with a good tan and thick moustache. He spoke perfect English with a vague accent. He had moved to Tiny-Town to manage a manufacturing facility, one of the few large employers in town. My wife and I were the only folks in Tiny-Town who had ever been to Turkey. We hosted a foreign exchange student from Egypt. She spoke French. Erol talked of the Ottoman Empire, the vast kingdom that had played a mighty international role until decimated — chopped into portions and doled out, following the First World War. Those, he believed, were his progenitors, the Ottomans of old, not the beaten down, bitter Turks of today. (His words.)

We avoided it for a good while, for good reason, but eventually we began to talk, inevitably, about religion. While he never attended any masque, and did not pray five times a day, Erol did, to some degree practice his Islamic faith. And I had come to town as the pastor of the Presbyterian church.

We both enjoyed those talks. I had drawn a good bit from the springs of the Sufi tradition, a minor sect of Islam know for their whirling dervishes and for giving us all the poet, Rumi. So we had a bit of common ground. We mixed poetry, spirituality and the practice of religion in talks that, in all probability seem far more profound now than they ever really were.

Erol became my token Muslim Friend. Very politically correct … Easy to site as a fictional authority, when in a conversational jam. We lost touch when my career moved me on.

My point, of course, is that I did have a true Muslim friend. For a time, we shared a journey. Some poetry, some spirituality, a bit of heart mixed in with 6:00 A.M. ice times and tennis tournaments. And now I am asked to consider a ban against all Muslims; now I am encouraged to distrust anyone from the middle-east, now I buy an AR 15 anti-personnel weapon in case Arab terrorists attack our little town here in MT. Now I am asked to carry a banner of hatred against my old friend. Brother against brother. I didn’t ask for this. I didn’t ask for North and South Korea, or North and South Viet Nam, or the Berlin wall or the damned Mason-Dixon line. I don’t want to choose between our national security and my old friend. I’m not sure I can accept that dichotomy.

I’m not sure I have to.

A Refugee

Yes, I left.

I left because staying home was too dangerous.

I left with what I could carry.

I carry nothing now.

I sleep where the day’s journey ends.

The roads are barricaded,

The barricades are guarded,

The guards are armed.

I left my home to make another,

But there is no other.

I sling my pack beneath my head

And wrap up in my blanket

And long for home.

I left my olives and jasmine

For fear of murder.

But this is just murder

Elongated,

Stretched over roads and soldiers,

Stretched over old bones

And remains of sinew and tissue,

Stretched over time, over continents,

Stretched over centuries,

Stretched over how many mass graves,

Scimitars and improvised explosive devices.

Stretched over Crusaders, Moors and Knights of Malta.

Stretched over dark seas of oil

Roiling beneath the sand,

Stretched over endless war,

Stretched thin, stretched taut

For my murder.

I will not live

To see my home again.

And there is no other.

Feeling Good

I used to know a song: “It Feels Good, Feeling Good!” Man, does it ever! I have been down for over two months – inflamed bowel. Ugh. So, now, after tentatively identifying diverticulitis, and a few rounds of antibiotics, I’m feeling good! It takes a longer time to heal, nowadays. So I’ve been sick, getting better. Rehabbing a bit.

The past year has been tumultuous (can’t help but reflect while holed up on the can…) with many curves, but we have managed to land exhilarated at a rest top on the ski run.

As you gradually get better, you realize that you’ve been in a reposed state for weeks, doing next to nothing, preoccupied with things you wanted to get done. Now with some of the old energy back, I can perceive a task, and ‘Get ‘er done!’

Feeling better does feel good.

Today skies are stone-faced. It might continue to lightly snow, it might pick up, it might die off. You don’t know, at 6500 feet altitude. Probably snow all day.

Cindy is reflective: Her mother died at 6:45 EST last night. They will probably wait til after the holidays for a memorial service in NH. It doesn’t look like I will be conducting the service. There is lots of death around, from TV to family and friends, and I admit I did get fixated upon it for a few days, esp. after learning of Melanie’s death, and reading 100 poems about death … BUT! There is also LIFE all around. And here I am, alive, today!

Hallelujah!

Melanie is Seventeen

Chuck Denison

11/17/15

Melanie is seventeen.

She wears her thin blonde hair long and straight,

Parted in the middle, like everyone else.

We skipped school and drove

All the way to Walden Pond for no reason.

But there we are, visiting Thoreau’s shrine,

The Spring lake,

The thick old woods.

The world makes no sense to us,

Everything seems absurd, and that has become our favorite word.

Friends are being Taken,

Forced to fight in jungles in Asia,

Our government is in collapse,

Our world is leaderless,

Our lives bore us.

Melanie is miserable, in palpable pain.

I want to fix it,

But I only hurt her.

We are seventeen:

We are new, pure, clumsy,

Untouched naïve.

What do we know?

I wonder what she was like at, say,

Thirty-two –

Her beauty softening,

Or mourning her lost waistline

In the full length mirror back of the closet door,

Forty-four.

Her niece tells me she was

A good mother.

Her niece tells me she died.

So I try to imagine

My seventeen year old Melanie

At fifty-eight,

Pale, emaciated,

Eyes fading, wet and yellow

Surrounded by her family,

Sitting up in a folded bed,

Tied to tubes, monitors and transfusions.

She is gasping for breath

Her daughter holds her hand

No priest is there.

I can’t stay for long.

It’s a sunny day

On Walden Pond,

And Melanie is seventeen.

Everything I Need to Know I Learned from TV

I know fifteen ways to kill a person with my bare hands;

I know that all Arabs are terrorists;

I know that pretty much everybody is screwing everybody;

I know that detectives really care about people;

I know that anything can be resolved in one hour;

I know that I am “special”;

I know there is a pill for what I have;

I know that, at 62, what I need is a retirement plan;

I know that my bank, and all banks, really care about me, too;

I know Jesus wants me to be rich and own a private jet;

I know that country singers are a real family;

I know the CIA is the only reason we are alive;

I know it ends well.

The Other One Was Better

I wrote a poem but tore it up.

It was full of things

I don’t want to know how to say.

About your failed life,

Your shriveled soul,

Truths we must never mention,

Feelings beyond impolite,

Words which, if you found them,

Would hurt me.

Unfound, they hurt me now.

So why write them.

But I know them to be true …

And I think about you …

Guess I’ll tear this one up too.

When words were anvils

for beating plows to swords

And men to action,

When thoughts were spring fed streams

Meandering their complicated courses

Running, connecting, joining,

Finally the river,

The deep river,

When nouns held shape and substance

When the thing and the name were the same,

When verbs ran and fought, floated and

Tickled, frolicked and fell

When description was an afterthought,

When women dreamed in words

And language could catch and hold the soul,

When words were all we had —

How rich we were then.

I started playing guitar on my mother’s old Silvertone Tenor guitar. One of the four strings was broken off, so it played a lot like a mountain dulcimer. And as soon as I got three chords down, I began writing songs. It was just natural enough to seem inevitable. I was twelve years old then … that was fifty years ago.

I can still remember playing that impossible guitar in that little knotty pine paneled den. It was an escape from all the tensions and conflicts that seemed to whirl all around my home, all the time. I was somehow safer with a guitar.

It became my solace. Down in that little den in Philadelphia I learned music and harmony from Peter, Paul and Mary. Back in Boston, through the crazy years of high school, I played guitar alone in my room night after night. I learned Beatle songs. The 60’s took over with irresistible music and momentum. Country Joe and the Fish. The Grateful Dead. James Taylor. Jim Croce. Gordon Lightfoot. Lobo (remember him?) Joni Mitchell. Crosby, Stills and Nash. Bob Dylan. Harry Chapin. The Dave Clark Five. The Beach Boys. Clapton. It became easier to learn the more I played. After a few years, I could play B Flat – sort of.

First time off to college, I dormed with a Johnny Winter nut. He played it just like Johnny. He loved the blues. I was interested. He needed someone to play the rhythm part. He patiently taught me 12-Bar Blues. So I could play the same basic chords (all three of them!) underneath, while Johnny Jr. tore up the neck, and I watched. I studied. By the time I quit college, I was ready to travel and start a blues band. In 1971. Hah!

I was playing blues ten to twelve hours every day in FL, coming home and listening to Segovia play Bach as I fell asleep every night. The music then was – mythic. It was pervasive, it called to us, it led us onward. More than anything I wanted to play a part in that great movement. I wanted to be an instrument, I wanted to call to people through the music; rather, I wanted the music to call to people through me. It had always seemed like an extra-nous, out of body experience to transcend myself in music, or to travel via imagination into the ether, and come back with a new song. It was somehow – thrilling. By nineteen I was earnest about a career in music.

Then a funny thing happened. In the back of my mind, I had always felt destined to become a Presbyterian minister. That apparent “destiny” had just always been there. I had no idea how it was implanted. Although I had occasionally attended Presbyterian Church growing up – at the insistence of my mother – it had never reached me, never moved me at all. The “power” of religion was miniscule next to the charismatic lure of music. But, by nineteen, my life was becoming fairly unlivable. I spent all day stoned, playing guitar. I made a little money installing lawn sprinklers in Lakeland, FL in the summer: it was brutally hot, dizzyingly hot; stand under the hose so you can think hot. I was stoned most of the time. I was in some trouble with the law, which I considered trivial and stupid, but which had the potential to lock me behind bars for years. I didn’t seem to be making any money playing blues, and the prospects weren’t looking all that good.

Somehow, underneath everything, the fire of faith had never gone out deep inside my soul. I knew that God was the meaning to all of life and to my little, personal life, and I knew Jesus Christ was my only real hope. “The chief end of man is to love God and glorify Him forever.” Westminster Shorter Catechism. So, after years of trying and wondering, I converted.

I really converted! Everything changed. New clothes, new hair, new language, new habits, and lots of broken old habits. One thing didn’t change: the music. Well – alright, the words changed. But within weeks of my new life, I was back on stage playing the same music with new words. Amazing Grace to the tune of House of the Rising Sun? Anyone remember that?

By Twenty I found myself, almost inexplicably and utterly unexpectedly in Bible School in North Dakota. I toured for two years with a semi-professional Gospel Trio, we were out every weekend and all summer, doing our shows at Pentecostal churches, camps, revivals, youth groups, chapels, all over the plains. I performed a great deal in those days, but it was all like an afterthought. Getting good was just a by-product of loving to play so much. It was always easy for me to play for hours. Still is.

So my musical aspirations changed direction. My neighbor Phil McHugh became an inspiration back then – he had some income from the family farm, and was determined to stick it out and make it in the intimidating world of industrial Christian music. He went on to write “People Need the Lord” a few years ago. I was looking at following with him, but something held me back. That “Calling.” What to make of it?

College and Seminary followed. I learned Greek, and I passed Hebrew. I wrote my papers and jumped through all the hoops and was ready to be ordained to the Presbyterian ministry, when I faced the Big Question in the big way. Which was it going to be? Sure, I could play a little and write some songs while I served Presbyterian churches as a pastor, or alternately, sure I could preach some and touch some lives while touring as a musician.

But what made the decision was the lifestyle. I had toured a little. I had several friends who had spent years on the road. I could see the havoc the road made of marriages and friendships and health; I could see the wreck these touring musicians made of their lives. I was newly married. I didn’t want to lose that love. I didn’t want to not know my kids, to be a Dad who stopped by now and then, often unexpectedly, for an awkward parental visit … and didn’t show when I was supposed to. I didn’t want to leave a string of savaged relationships as my personal legacy. Drugs, Sex and Rock ‘n’ Roll, the energy of Led Zeppelin, the reason for the Eagles to keep it up, just weren’t enough for me. I’d seen the broken hearts and lonely lives.

So I made my decision. The career decision. I opted to spend my career in mostly rural churches. I got to stay home. I didn’t have to travel until years later, when, kids grown and in college, I became a consultant to help lots of new churches. I went to my daughter’s soccer games and my son’s concerts. I knew a few of their teachers. I shared my love of music and words with my kids. I stayed home, and I invested my life in my family, a few friends, and a number of churches. I tried, with my career, to help people to connect with God. A simple enough mission statement. Church was the primary avenue for that.

Now I am sixty-two! I’ve retired. Looking back, I have few regrets. I’ve learned a good deal about the music business. Had I invested that same forty years into Nashville or the music industry, I believe I would have “made it” in one way or another. I would have a network of friends and peers; similar to the one I have in the PCUSA. But I would have paid a price I was not willing to pay.

So, today I am back with the music. I play my guitar for hours most days. I write my songs, usually 3-5 per week. I send some off to Nashville. I am still trying. And I am only 62! I have lots of years to keep hammering at the cold, impervious walls of Nashville. I can perform, but I’d rather let someone else do the singing — and the touring. I’d just like them to sing my songs.

My family raised, my wife by my side after thirty-eight years, I have given up my church career to pursue the old first love: I am a songwriter.

I used to be driven. For some decades, I enjoyed it. I lived on adrenaline. Eventually the rush started to wear off. I’ve crashed a few times. But getting back up and going meant really going. 100 MPH.

I’m not driven anymore. I have time. I relax a lot. I can watch TV. A little … But the freedom I feel is more than a freedom from the pressures of a work week. I feel so free to just be who I am. The role of pastor comes with so many expectations and demands, so many unspoken rules, and I am free of all of that. Free from all the politics of Presbyterian Women. Both of my parents have been gone for several years now, and I am beginning to feel free from the pressure and power they exerted in my life as well. Being broke is even a freedom in itself. I get healthier all the time.

Like Peter Gibbons, the hero of Office Space, I’ve dreamt of the chance to do nothing. And like him, when I finally get the chance, “It’s better than I ever hoped!” I am putting most of my time into music now. That’s always good for me.

Recent Comments